Discovering the Site

CHRONOLOGY

The Cerro de San Vicente, the place where the city of Salamanca originated, constitutes an archaeological site that hosts extensive historical occupation, whose main remains correspond to protohistory, medieval, and modern times. It was during the First Iron Age, between the 7th and 5th centuries BC, when a stable settlement was built in this location, following patterns similar to those of other settlements established in the middle Duero valley during the same period, although there are indications of an earlier occupation from the Late Bronze Age (end of the second millennium BC).

LOCATION

The placement of the settlement was not accidental and was due to a series of favorable factors for human settlement at that time. Among them, its position next to a ford and the wide plain formed by the river Tormes at this point stands out, along with a good visual command of the surroundings and the economic possibilities of the area, which allowed for the development of a mixed economy with abundant riverside forests and holm oak groves nearby. Furthermore, it was located on the natural geographical corridor that would later be known as the Vía de la Plata, a communication route through which various cultural currents passed throughout History. Its strategic location, dominating the Tormes valley and the Cerro de las Catedrales itself, motivated subsequent occupations of the site, from medieval to contemporary times.

EXTENT

The settlement of Cerro de San Vicente extends mainly across the western end of the hill on a flattened plateau that rises about 30 meters above the river, covering an area of about 2 hectares. It was surrounded by a rocky escarpment naturally shaped by the river courses flowing around it. Its most accessible flank was reinforced by an arched defensive wall that protected the northeast of the hamlet for about 90 meters.

EVOLUTION

The great sedimentary thickness of the preserved archaeological strata, exceeding two meters and corresponding to successive habitat phases, allows us to speak of several centuries of occupation in this enclave, which evolved until the dawn of the Second Iron Age. From this moment (4th century BC), most of its inhabitants, due to the lack of space in the original location caused by a significant demographic increase – despite the fact that the hamlet had expanded beyond the wall's delimited area – moved to the neighboring Teso de las Catedrales and built the renowned castro of Salmantica, the substratum of the current historic city, leaving the original site converted into the adjacent neighborhood possibly alluded to in classical texts regarding Hannibal's military expedition through these lands.

THE PROTOHISTORIC SETTLEMENT

ECONOMY

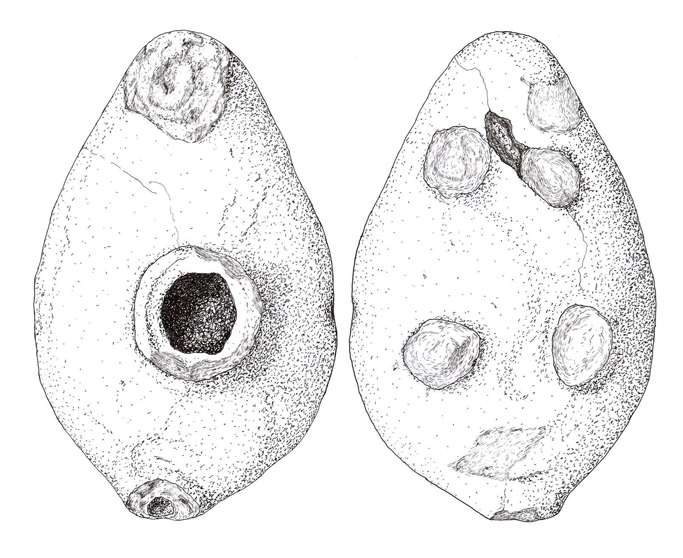

The survival of the people who inhabited Cerro de San Vicente during the First Iron Age was based on the agricultural and livestock exploitation of their surrounding territory. Among the main economic activities, the cultivation of cereals such as barley and the collection of wild tree fruits, especially acorns, stood out; these were stored in constructions attached to houses and used as granaries. Their relevance within the group's economy is attested by the frequent appearance of hand mills and grinding stones in all contexts of the settlement. We know that the agricultural use of the land near the settlement implied significant deforestation of pines and oaks, while riparian species (elms, willows, and poplars) were maintained for the exploitation of resources offered by riverside forests.

They were sheep herders, and the majority finding of adult bones speaks of their consumption as meat, independent of the utilization of other products such as milk and its derivatives or wool. The abundance of this species could point to a transhumant practice, with seasonal displacements across the territory in search of fresh pastures via natural livestock routes like the one that gave rise to the Vía de la Plata, despite lacking conclusive evidence. They also had a significant bovine and porcine herd, and to a lesser extent, equine. Bovines were used both for their meat and hides and for their exploitation and use as traction and pack animals, as demonstrated by the adult age of the remains found and the frequent deformities detected in bones due to continuous loading. Dog bones have also been found, sometimes with traces of having been consumed. This pastoral work was complemented by hunting wild species from the area (deer, rabbits, etc.). Trade outside the settlement is not documented, but external exchange practices are inferred by the presence of certain imported elements (painted ceramics, double-spring fibulae, iron objects, and in the final phases, wheel-thrown pottery), through the natural corridor later known as the Vía de la Plata, which were incorporated into the local culture.

The material culture of the inhabitants reflects the various artisanal tasks developed, besides constituting a factor of cultural identity. Among these, pottery stands out, its evidence holding the most relevant position among household items due to its abundance. Ceramics are characterized by being handmade, and common storage and cooking vessels, which contrast in their coarseness and simplicity with fine tableware featuring more careful finishes and a unique decoration made with impression, incision, and comb techniques, can be distinguished. Within this group, the painted pottery found at the site stands out for its cultural significance, with a decorative and ritual character, undoubtedly demonstrating the social prestige of its owner, whose striking geometric motifs help to relate this culture to other similar ones of the European First Iron Age. For its part, metallurgy is attested by remains of crucibles and small bronze objects, such as awls, fibulae, needles, or arrowheads. The use of iron was still very sporadic, and data proving its employment is very scarce. The rest of the economic practices were reduced to a textile craft industry (as demonstrated by the appearance of spindle whorls and loom weights), and the elaboration of simple utilitarian tools with bone materials (spatulas, handles, awls) and stone (mills, weights, adzes, polishers, hammerstones) or ornamental objects (necklace beads, pendants).

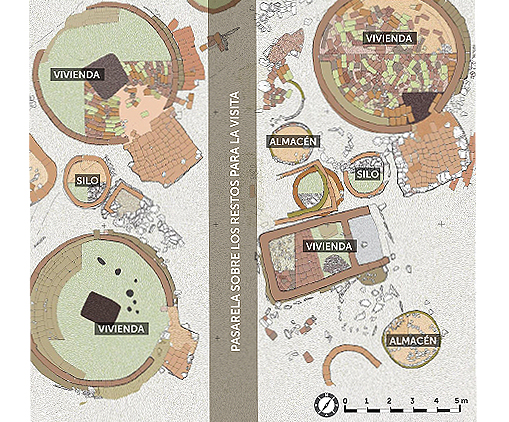

URBAN PLANNING

Within the settlement, constructions seem to follow a certain order that allows us to speak of incipient urban planning. In the exposed area, four complete dwellings and up to 9 auxiliary domestic structures linked to them have been identified. All of them are distributed in two aligned bands around a transit space or “street,” following a northwest-southeast axis about 3 meters wide observed for at least 20 meters in length. The houses and their associated auxiliary structures (storerooms, pantries, ovens, etc.) are concentrated, forming complexes (domestic units) that met the basic and functional needs of the family entities in which the group was organized. Considering the concentration and distribution of the hamlet observed in archaeological excavations carried out at different points of the site, this settlement could have reached a population of over 250 individuals.

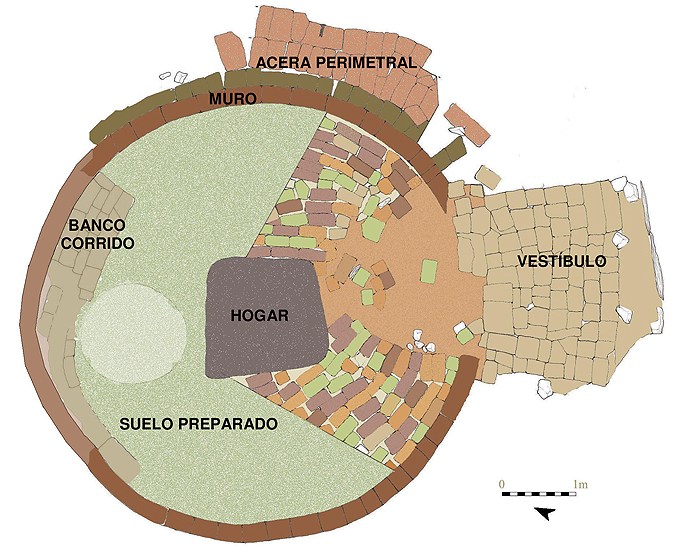

ARCHITECTURE

One of the elements that best defines the protohistoric settlement of Cerro de San Vicente is its mud and adobe architecture, despite being located in an area rich in stone that has served as a quarry for centuries. Most of the houses are circular in plan, between 4 and 7 meters in diameter, although they coexist with others of rectangular plan, 4.5 to 6 meters long by 2.5 to 4.2 meters wide. Inside, as the most identifiable elements of domestic furniture, they house a continuous bench attached to the wall that served as a seat and bed, and a central hearth, slightly raised from the pavement, prepared with thin superimposed layers of clay, where fire was lit to provide light and warmth to the dwelling. Interior lighting was complemented, according to archaeological finds, by lamps that possibly used animal fat as a fuel source. The walls often appear decorated with painted ornamental geometric motifs similar to the iconographic repertoire of the peoples of the European First Iron Age.

As shown in the stratigraphy of the settlement, over time, the architecture, despite its simplicity, became more complex with contributions such as the incorporation of adobes at the base of the interior floors and the construction of vestibules in the threshold area. Smaller structures, corresponding to silos, granaries, or ovens, are also built with adobes, rammed earth, and stones, and have average dimensions of 1 to 2 meters in diameter. Overall, the main construction material in the settlement's architecture is mud (adobes and rammed earth), complemented by local stone (siliceous sandstone) or collected from the vicinity (slates and pebbles).

SOCIETY

The analysis of the data obtained from this site points to a society that was basically egalitarian and organized around family groups, given the homogeneity of the settlement's architecture and material culture. The notable thickness of archaeological sediments generated by the superposition of constructions from the same period proves its stability over several centuries and its success in exploiting the surrounding territory. To date, the funerary rites in the settlements of this culture are unknown, except for infant burials beneath the floors of houses, a practice of clear symbolic and familial meaning that has been documented in Cerro de San Vicente with an inhumation belonging to a neonate.

THE CONVENT

ORIGIN

After an abandonment of nearly twelve centuries, the Cerro de San Vicente was reoccupied in the Middle Ages, in a very early phase of the city's repopulation, probably during the reign of Ramiro II, in the 10th century, when the convent of San Vicente emerged, a pioneer among Salamanca's monastic foundations. Although traditional historiography places its origin in the Visigothic era, archaeological remains and historical documentation have not corroborated this.

CLUNIAC PRIORY

In 1143, the convent was transferred to the Order of Cluny, as evidenced by King Alfonso VII's donation charter to Peter the Venerable, abbot of the Burgundian monastery. This annexation consolidated the city as a relevant monastic settlement, given the order's importance at the time, and favored its repopulation. Despite Cluny's progressive decline in the Late Middle Ages, its prior continued to enjoy certain prerogatives in municipal government for several centuries, being the most prominent institution in the western sector of the city.

BENEDICTINE MONASTERY

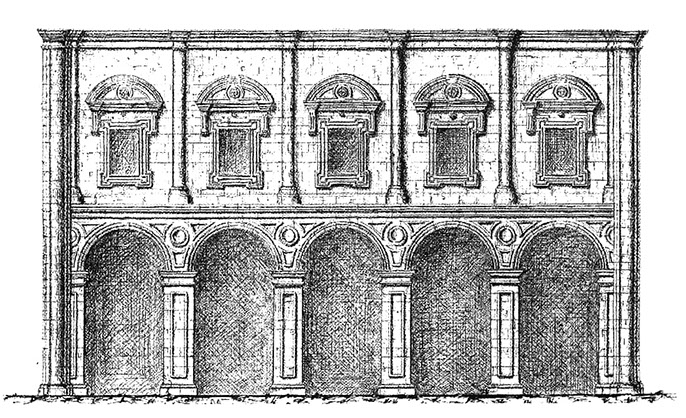

In 1504, under the patronage of the Catholic Monarchs, the convent was annexed to the Reformed Benedictine Order, with its headquarters in San Benito el Real de Valladolid. Immediately afterwards, in 1505, it became a university college, which involved the reconstruction and reform of the building to adapt it to the new collegiate needs. From this moment on, the monastery enjoyed a period of splendor that materialized in the undertaking of major works that would make the convent of San Vicente one of the great architectural complexes of the city of Salamanca.

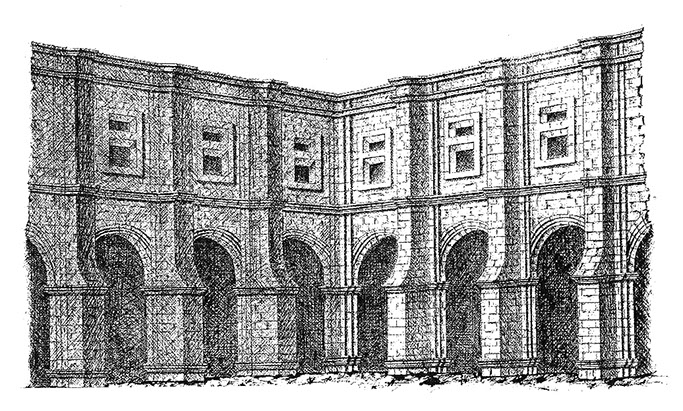

CONSTRUCTION OF THE COLLEGE

The renovation of the building included all the necessary infrastructure of cells and dependencies to house the novices. Construction began in the mid-16th century in the cloister area, which was reformed and expanded from 1570 onwards. During this same period, the monastic community acquired the adjoining lands to the west, known as “el castro,” which they used as a garden and orchard, where they built a viewpoint and a recreational house.

At the beginning of the 17th century, a new wing serving as a guesthouse, called the gatehouse (portería), was added, forming a large rectangular pavilion whose walls were attached to those of the pre-existing building. The construction of the new church, replacing the previous medieval temple, began in 1610, but extended until the first third of the 18th century, concluding with the construction of the church choir and the sacristy. The resulting monastic complex, of great beauty and architectural and artistic value, was considered one of the monumental jewels of the city.

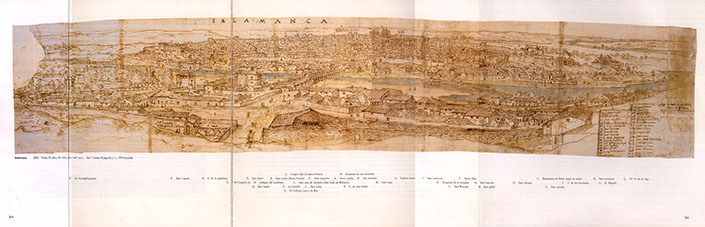

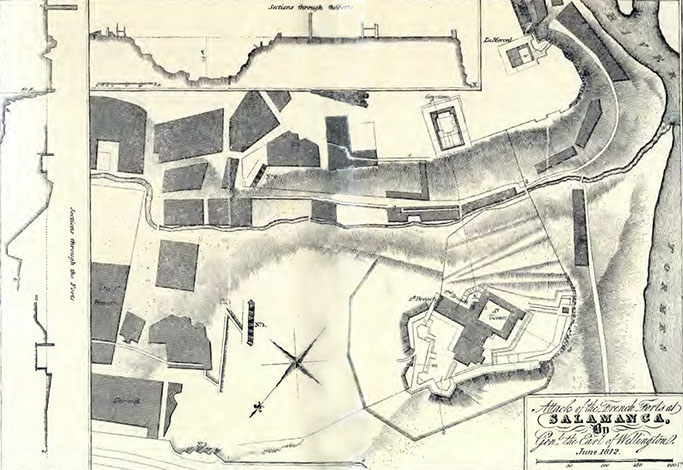

MILITARY FORT

The strategic location of the San Vicente monastery led to its occupation by Napoleonic troops, who transformed it into a fort in 1809, during the Peninsular War (Guerra de la Independencia), just like the convents of San Cayetano and La Merced, located on the neighboring Cerro de las Catedrales. The new military use led to its remodeling and the installation of fortified defenses in its surroundings, using demolition material from the nearby hamlet, which are known through 19th-century military plans. The final outcome of the Battle of Salamanca in 1812, in which Anglo-Hispano-Portuguese allied troops defeated the French army, caused its destruction and ruin, turning it into a symbol of the devastation suffered by the monumental city, which lost a third of its built-up area in this war.

CONTEMPORARY PERIOD

After the end of the Peninsular War, the Benedictine monks tried to rebuild what remained of the convent building, until in 1835 they completely abandoned their unsuccessful attempts, a situation contributed to by the disentailment policies of the governments of that period. Thus, the ruins of the distinguished building were left abandoned and exposed to unchecked looting of its fabric, so by the last third of the 19th century, no remains of artistic interest were preserved.

From this date, the area began to be colonized by the population, who created, upon and largely reusing the rubble of the monastery, a popular neighborhood of small constructions that lasted until a few years ago and erased any trace of historical urban planning until the recovery project began in 1997.